Variables

A variable is a named memory.

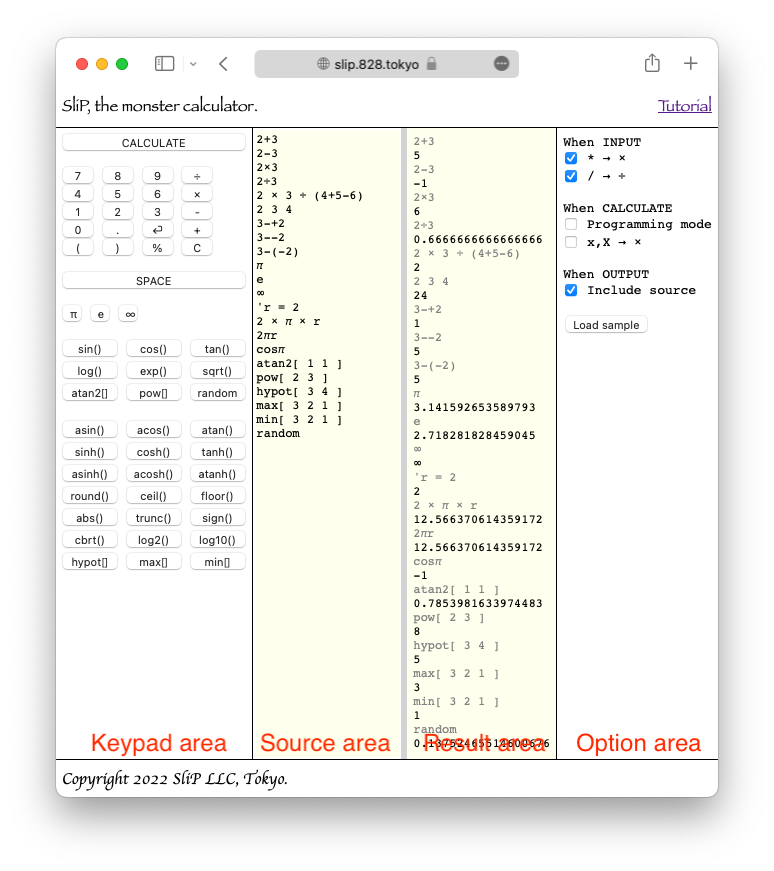

For example, to make a variable named r remember the value 2, you would do the following

'r = 2

Now let's enter the following equation

2 × π × r

Pressing the CALCULATE button displays the value 12.566370614359172, which is the circumference of a circle of radius 2.

This equation can also be made to look like the following using the abbreviation of the multiplication operator above.

2πr

The names of the variables are actually a bit complicated, but they generally look like the following.

Basically, it starts with a letter, followed by repeating letters or numbers, and ends with a space.

For example

abc

na12me

These names have not yet been defined and will result in 'undefined' error.

Greek letters and ∞ are used with only one letter. For example, abπcd∞ef is five names: ab, π, cd, ∞, and ef.

Arithmetic Functions

Trigonometric, exponential, logarithmic, and other arithmetic functions are available. They can also be entered from the Keypad Area.

Let's enter the following equation

cosπ

Pressing the CALCULATE button displays the value -1.

The arithmetic functions atan2, pow, hypot, max, and min require two or more parameters. You can pass parameters to them in an array.

atan2[ 1 1 ] // → 0.7853981633974483

pow[ 2 3 ] // → 8

hypot[ 3 4 ] // → 5

max[ 3 2 1 ] // → 3

min[ 3 2 1 ] // → 1

Primitives

'random' is also available, it is not secure enough to be used in cryptography. It should not be used for security-related purposes.

random

Programming mode

SliP is also a programming language; it is a functional language influenced by Lisp.

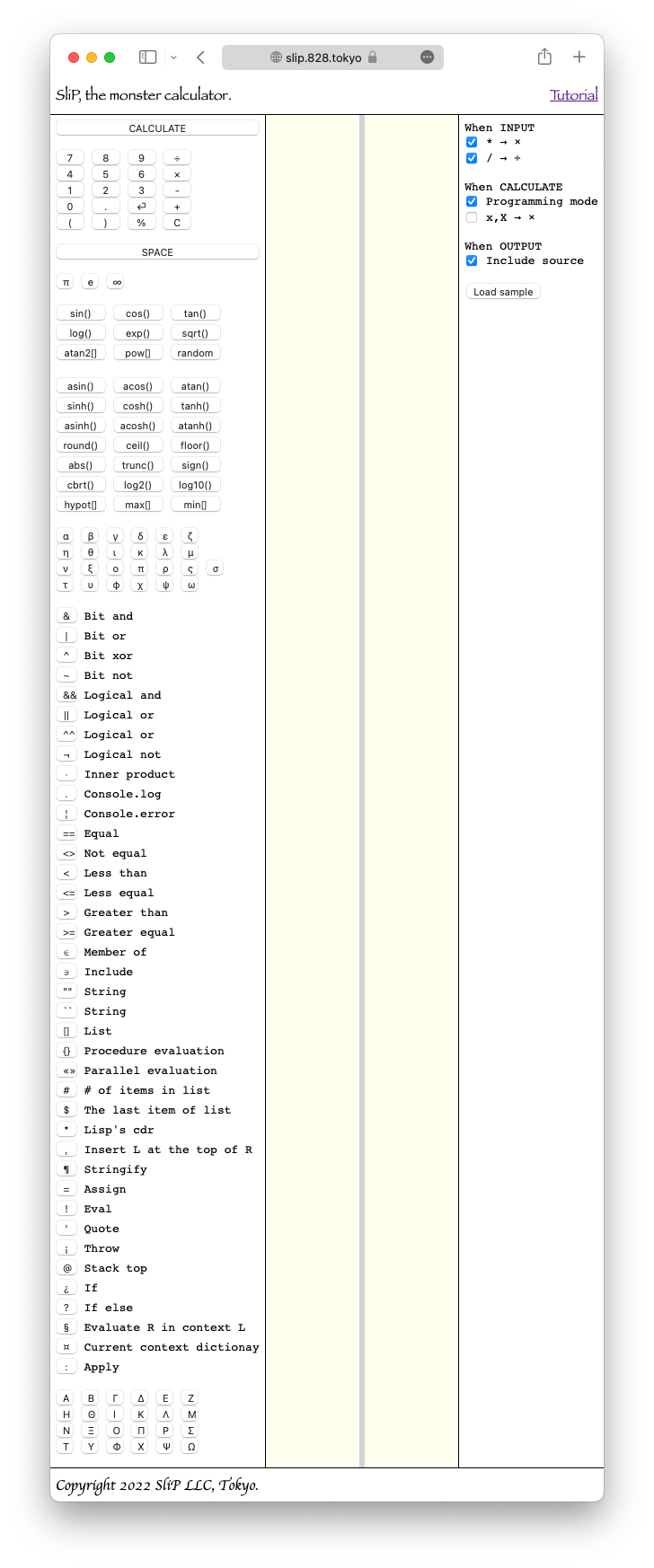

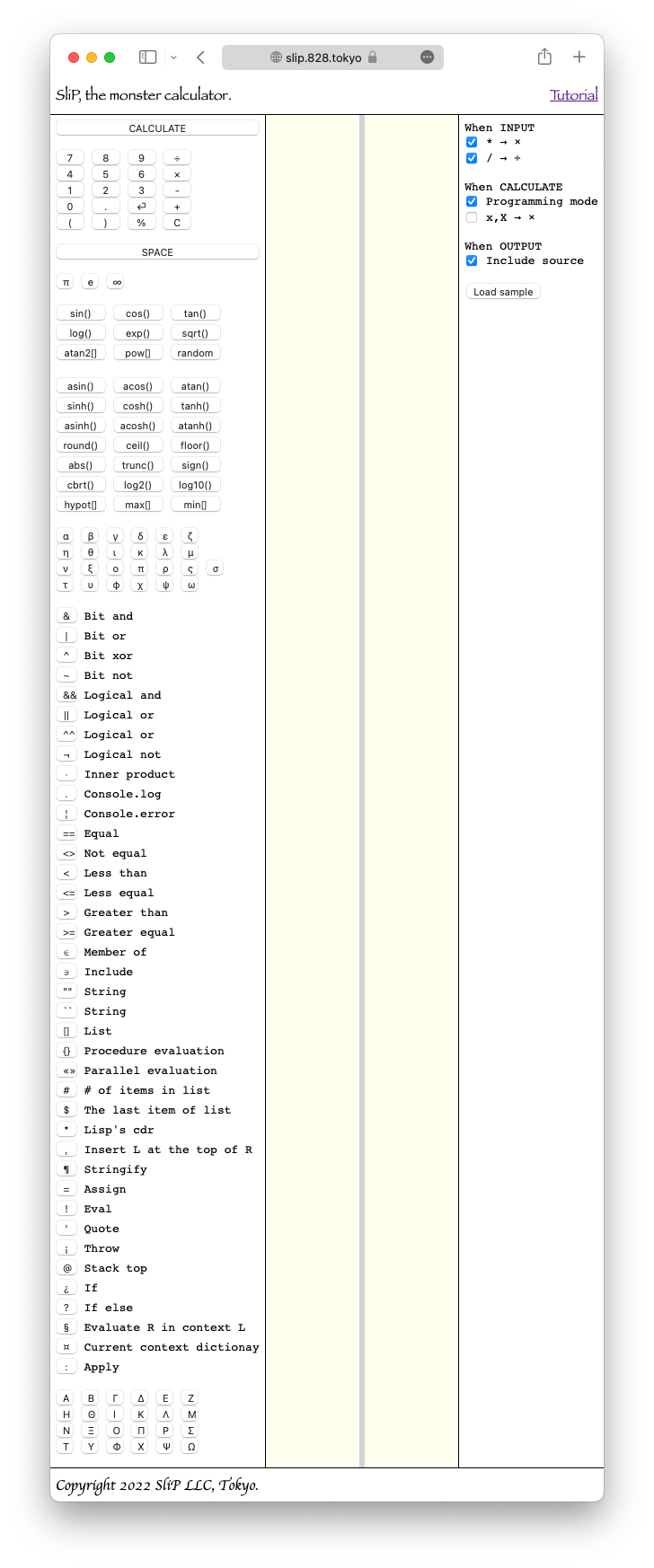

You can use this feature by checking the 'Programming mode' checkbox in the Option Area. If checked, the Keypad Area will look like the screenshot below and you can easily enter various arithmetic symbols.

Spanning lines

Expressions that had to be written to fit on a single line in NORMAL mode can be written in PROGRAMMING mode by enclosing the entire expression in parentheses and spanning lines.

Basics

Programming SliP is done by evaluating what is called an SliP object.

The main SliP objects are

- Numbers

- Strings

- Operators

- Names

- Sentences

- and etc.

The numbers, strings, and operators return themselves when evaluated.

3 // → 3

"abc" // → "abc"

× // → ×

A list of SliP objects enclosed in parentheses is a sentence, and when evaluated, various calculations are performed according to the operators in the sentence.

First, let's look at a function that returns the value of its argument multiplied by two as an example.

( 'mul2 = '( @ × 2 ) )

The meaning of this sentence is to assign the expression '( @ × 2 )' to the name 'mul2'.

' is called 'quote' and when evaluated returns the next SliP object without evaluation.

'@' denotes an argument.

Let's use the function we just defined named mul2.

( 3 : mul2 ) // → 6

Name returns the assigned SliP object when evaluated. In this case, the expression is ( @ × 2 ).

: is infix operator, which evaluates the right side (R) with the left side (L) as its argument.

NIL

SliP does not have a boolean type. Instead, empty lists such as [] are called NIL and treated like false in other computer languages.

A dummy SliP Object with a display name of T may be used to represent something that is non-NIL.

Therefore, all boolean operators such as == return NIL or non-NIL.

Recursive

Let's try to calculate the factorial of N by programming.

The factorial of N is the factorial of (N-1) multiplied by N. This can be expressed in SliP as follows.

( 'factorial = '(

@ == 0 ?

[ 1

( @ × ( @ - 1 ):factorial )

]

) )

( 4 : factorial ) // → 24

==

This operator returns non-NIL if the left and right arguments are equal, NIL otherwise.

?

This operator evaluates the first element of the right argument if the left argument is non-null, otherwise it evaluates the second element of the right argument.

String

SliP strings are available in two notations. One is to use " and the other is to use `.

"This is `STRING` enclosed in \"" // → "This is `STRING` enclosed in ""

`This is "STRING" enclosed in \`` // → `This is "STRING" enclosed in ``

Dictionary

SliP also has a dictionary type.

There is no native notation for describing dictionaries, but they can be created from JSON using 'byJSON' operator.

When pulling dictionary values, you can use strings and names as keys.

( 'json = `{

"a" : 1

, "b" : "The String"

, "c" : [ 2, "Another string" ]

, "d" : {

"A" : 3

, "B" : [ 4, "Yet another string" ]

}

}`:byJSON

)

// → { a : 1 , b : "The String" ...

( json:"d" )

// → { A : 3 , B : [ 4 "Yet another string" ] }

( json:'d )

// → { A : 3 , B : [ 4 "Yet another string" ] }

Context

Contexts are the environment in which variables are evaluated.

Each context has its own dictionary and is a chained structure.

When looking for a value for a variable, if it is not found in the variable's own dictionary, it will go to a higher-level dictionary.

Procedure evaluation

If you list sentences in {}, they are evaluated in order.

A new context is created at this time.

A list of values for the statement being evaluated is returned.

{ ( 'a = 2 )

( 'b = 3 )

( a + b )

}

// → [ 2 3 5 ]

Parallel evaluation

If you list sentences in «», they are evaluated in parallel.

No new context is created.

« ( 'a = 2 )

( 'b = 3 )

( a + b )

»

// → [ 2 3 5 ]

Difference between Procedure and Parallel

Operator ¤ creates a Dictionary object from the current context.

¤

// → {}

{ ( 'a = 2 )

( 'b = 3 )

( a + b )

}

// → [ 2 3 5 ]

¤

// → {}

« ( 'a = 2 )

( 'b = 3 )

( a + b )

»

// → [ 2 3 5 ]

¤

// → { a : 2 , b : 3 }

After parallel evaluation, a new variable is registered in the current context.

Finally

We are currently working on the reference. We hope you enjoy SliP.